Get Rid of That Bottleneck Using Modern Queue Techniques

Learn how to examine several bottleneck situations related to the hosting machine and its limitations and come up with queue-based solution to them.

Jan 10, 2019 • 19 Minute Read

Introduction

There are common situations in which your software, even when properly written and debugged, will face bottlenecks.

These bottlenecks will mostly be related to the hosting machine and its limitations. In some cases, we may limited by the capabilities of our CPU. In other cases the limiting factor will be our machine's disk I/O capabilities. RAM can also become a bottleneck, even for today's monstrous machines.

In this article, we will try to examine several of these situations and come upon a queue-based solution to them.

This article will serve as an “overview” rather than being specific to any technology (though it will mention the relevant technologies). If you feel like a specific topic is of interest to you, please drop me a word in the comments section, and I will try to provide a follow-up article.

Let’s get started!

Common Use Cases

The use cases we will examine are the following:

- Managing the consumption rate of data per client, through shifting from push to pull.

- Making unreliable messaging between software components reliable.

- Introducing load-balancing to our system, using queues and multi-instance (of software components) deployment.

- Utilizing resources in parallel to process more data per unit of time.

There are more use-cases where queues are being used. However, this article being an overview, we will focus on the most relevant ways of using queues for minimizing bottlenecks.

Shifting from Push to Pull - Preventing Client Overload

We all make the mistake of writing a piece of code to which we send requests.

Writing that code is not the problem, of course. The problem arises when we fail to consider the scenario in which this piece of code has to process more requests than it can handle.

In cases where there is a direct connection between a message producer and a message consumer, if a producer produces more messages than the consumer can consume, several things can happen. The diagrams below will cover these cases in detail.

In case the producer waits for the previous message to be fully consumed, subsequent messages will be produced with delay.

If the producer doesn’t wait for the previous message to be fully consumed, following messages will be produced on-time but consumed with delay.

In both scenarios, an in-process bottleneck will result. This is bad for performance. A bottleneck could lead to a bloat in RAM usage on whichever side (producer or consumer) the messages are waiting to be consumed.

The bottlenecked process uses so much RAM that it slows down as paging takes place, potentially blocking the entire host machine.

Queue-based architecture

So up to this point, I was the bearer of bad news. Now the good news — these situations can easily be optimized using a queue.

Let's take a look at the following proposed architecture:

In the diagram above, you can see that the message producer(s) and message consumer(s) are not communicating directly.

The message producer produces messages and pushes them into a queue once they are ready.

The message consumer then consumes messages as soon as possible by pulling from the message queue.

Evaluating the new design

Let's see if this design handles the problematic bottlenecks from before.

To begin with, messages will no longer face a delay in being produced, assuming our queue design is robust, which, if we are using technologies such as MSMQ or Apache Kafka, is a fair assumption.

Furthermore, our consumer is still able to consume just as many messages as before but now has control over the rate of message consumption.

This is done without “bloating” RAM and risking an out-of-memory exception, as pending messages are stored in the queue instead of in processes RAM. We will consider enhancing our architecture to increase message consumption rate a bit later in this article.

Seems nice, right? This architecture outsources our message production/consumption bottlenecks to a third party technology, thus making our software platform more reliable (i.e. reduced risk of out of memory exceptions).

Lets see what other benefits queues can offer.

Reliable Messaging Systems

The previous topic, while being related to message delivery reliability, did not address the reliability concern directly.

It helped us achieve better system reliability as it taught us how to handle the scenario in which the message production rate exceeded the message consumption rate.

Let’s now take on the challenge of making messaging explicitly more reliable in our system.

It is very common to see systems passing messages directly between processes.

I will not completely dismiss that there are use-cases in which such a scenario may be desirable in your system.

However, for common messaging requirements, this software design is flawed.

First of all, it requires the producing service to be familiar with the consuming service. That means that our producing service has either a configuration or service discovery mechanism.

We will have to write code that behaves according to its configuration, manages endpoints (“discovers” new endpoints, load-balancing traffic among them), and basically has built-in additional infrastructure modules.

I claim that these concern should remain in the realm of DevOps, and not software design. Service discovery, load balancing, dynamic system scaling and reliable messaging should be taken care of by the infrastructure managed by our DevOps team!.

I believe that a software engineer should focus at the algorithmic problem he is trying to solve, and simply declare the messages he wants to consume and have the infrastructure deliver these messages to his code.

In the same way, when the developer's code has something to say to the world (i.e. a message), it will simply produce a relevant message to the infrastructure and move on with its algorithmic problem solving.

Using a decent queue technology like Apache Kafka — which is much more than a queue actually — will allow us to separate the concern of system-wide reliable messaging from our code base and outsource that concern to a proven, mature technology that specializes in reliable message delivery. Having done that, we will also have created a healthy integration point between our software development team and our DevOps team from the standpoint of the product development life cycle.

Now - I don’t mean that its a healthy integration point from social reasons, but from the product development life cycle aspect.

Our DevOps team will deploy our software to their environment and provide feedback on messaging issues, bottlenecks, and other unacceptable messaging delays relaying even before our version has reached the QA team! Possibly even as part of automated build test on an environment “closer to real-life” than the developer's environment.

Early detection of problems = money saved.

Modern queue technologies have message delivery acknowledgment transparently built in, meaning that the entire process of making sure a message reaches its destination is completely handled.

To summarize this topic:

I’ve proposed using queues as a means of interprocessing communication among system services, especially to increase message delivery reliability and discussed some of the benefits of using a mature message queue technology to handle our messaging requirements.

I’ve also posited that such a platform should be completely outsourced to the DevOps team, freeing up the software team to focus on the algorithmic problem at hand instead.

Lastly, we established that a queue-based messaging infrastructure enables scalablity, fault-tolerance, and load-balancing in a software system.

Load-Balancing

Load-balancing is definitely something that can be achieved using queue technologies (again, please take a look at Apache Kafka).

Without using a queue, assuming you introduced an additional service instance to your system, you will have to introduce a load balancing mechanism as well:

This load balancer will have to take care of:

First — “knowing” which service instances are available. This will usually be done either by service configuration or by a service “discovery” mechanism.

Both these solutions require additional development and are error prone. Not to say that these approaches are not valid — but they require careful attention to specific details (e.g. service state — did a service crash?).

Next — it will need to be able to evenly spread messages among available service instances. That means that it will usually need to “remember” how many messages each service got (unless it is randomly sending messages to instances).

Laslty — the load balancer will be the only entity which can take care of message delivery acknowledgments as only he knows which service should acknowledge each message.

And these three tasks I’ve just mentioned would need to be done for each service that we want to run more than one instance of at a given time!

Ok, what about an alternative? :-)

What about using a … message queue?

I propose using a message queue per each message type.

This means that all messages of the same type are produced into the same queue.

In turn, all messages of the same type are also consumed from the same queue (obviously, as they are only stored there).

Your system services only need to know the queue connection details and relevant message queue name(s).

That means that introducing additional service instances to your system to tackle a bottleneck will be as simple as spawning a new service instance (assuming you do not store service state in-memory). That’s it! As the new service is establishing a connection with the queue, the queue will distribute messages among the instances for you (per your configuration).

Rather simple, right? We’ve increased our systems scale and increased our throughput by using a queue as our load-balancer.

Now, please notice that this load balancing we’ve achieved can also be ignorant of its consumers capabilities to process data as they are pulling data from it at their own rate!

Parallel Processing

The last use-case I will discuss in this article is the case of bottlenecks caused because of “large” computations.

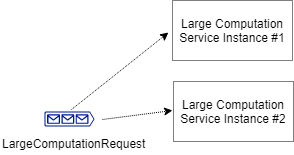

In the case of a “large” computation that cannot be broken down into smaller, separate parts, we will probably have to scale our system by bringing additional online services which can compute at a “large” scale.

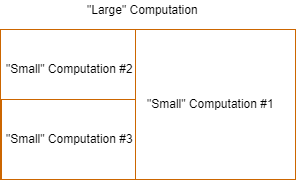

However, often there also may be computations which can be broken down into separate, “smaller” computations that can be performed separately.

With such computations, as I’ve just mentioneded, our system could be optimized by processing several “smaller” computations separately, in parallel, and then combining the results of these computations into a final result for the entire “large” computation.

Please keep in mind that parallelism is usually limited. You cannot just “break” a problem into as many “smaller” problems as you desire and just throw these at your CPU.

Each CPU has a physical thread count which should be taken under consideration when performing a computation in parallel. In case you don’t use all available CPU physical threads, you are probably under-utilizing your resources.

But be careful. In case your software handling large-scale computation requires more threads than physically available in your machine, you will pay the overhead created by context-switching.

But how will a queue help us here?

Again, just as mentioned before, when discussing separation of concerns between the software and DevOps teams, queues can help us write code that is agnostic of the environment it is hosted on.

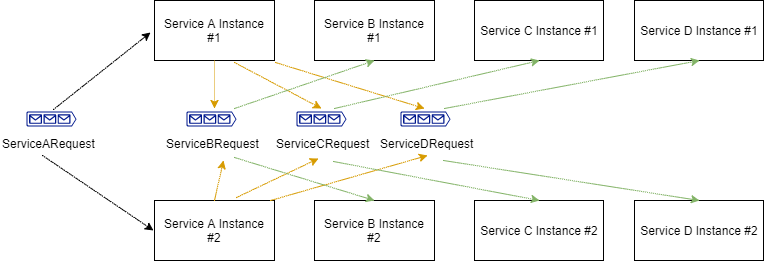

Consider the following example:

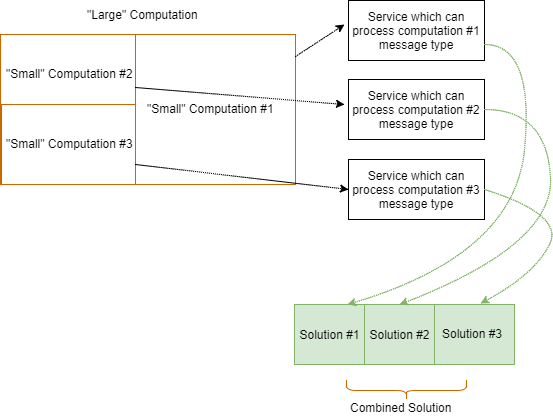

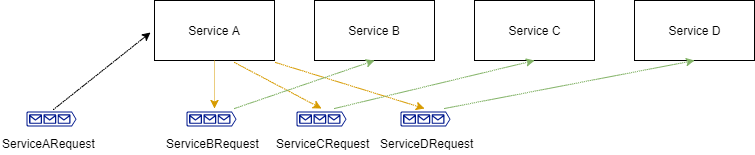

Our system is handling “large” computations. Service A receives input messages which he knows how to “break down” into three discrete “smaller” computations, which are performed by Service B, Service C and Service D.

Our system runs on a machine with eight available physical threads. That means that optimally we would like to have eight computations done in parallel.

Our software developers only need to concern themselves with writing the application in a way that allows performing the three discrete computations in parallel. That means that each different computation should have a dedicated message queue and a service which reads messages from this queue and processes them.

That’s all from the developer's point of view.

Now, on the DevOps side, we would like to make sure that two things happen:

- All message queues are created.

- The system is deployed with the correct degree of parallelism.

For the example above, as each message can be broken down to three “smaller” messages, we would like to have three service instances brought up (one for Service A, one for Service B and one for Service C) and be ready to receive messages per each “large” message. So we have three physical threads plus one physical thread = four physical threads per “large” message.

Having eight physical threads at our disposal, we can safely bring up an additional instance of service A, an additional instance for Service B, one more for Service C and finally an instance of Service D.

Our system will then look like this:

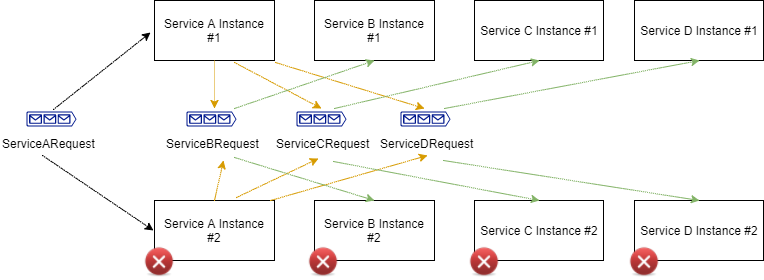

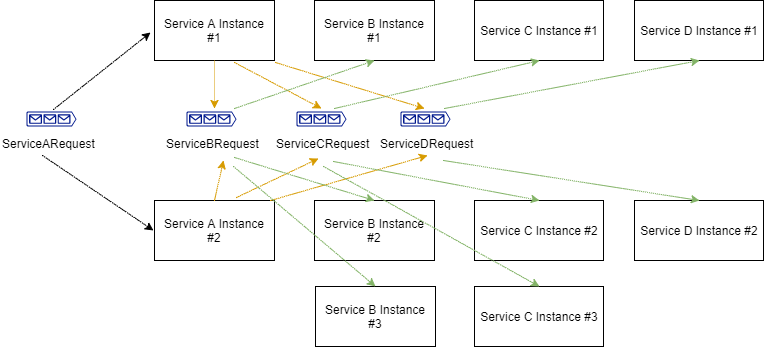

Now, what happens if need to scale down and be hosted on a machine with lower resources? This is not a software problem; not a single line of code will be modified. Instances can be taken down (in the diagram below we are bringing down four instances — reverting to the above deployment).

What about scaling out into additional machines? Not a software problem again, as no code will be written! Bring up additional services and point them at your message queue. That's all there is to it, realy.

That means that our developers need to concern themselves with “breaking” down problems into discrete computation units and making sure each computation type has a unique message queue.

If you follow these guidelines, your application will be able to perform computations in parallel, within the bounds of hardware resources (i.e. physical threads).

In Conclusion

There are many possible causes for system bottlenecks. In this article, I tried to address several of the most common ones, based on my software experience.

While the causes of such bottlenecks might differ, they do share some common features. We can typically use message queues to optimize these scenarios to the best of our hardware capabilities.

When combined, the practices described in this article can assist in building more reliable, robust software systems that support changing scale and that maximize hardware resources.

Thus, our message queue will benefit our code, making it smaller and more robust. It will also improve our product development life-cycle.

Furthermore, scaling our system will now become the domain of our DevOps team. And it needn't be more complicated than spawning additional service instances.

It can really be that simple :-)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this overview article on resolving bottlenecks using queue technology. You are more than welcome to send me requests for article topics or to leave me questions and feedback regarding anything I’ve written here.

Thanks for reading!

Kobi.

Advance your tech skills today

Access courses on AI, cloud, data, security, and more—all led by industry experts.