Distributed Graph Computation as Simple as It Gets with Apache Storm

In this guide, we will present you with Apache Storm as an implementation of a distributed graph computation infrastructure.

Dec 14, 2017 • 26 Minute Read

Introduction

Computations can be complex. Mostly for us, the human drivers of the software world. There’s even a whole domain of science centered around problem solving and computations — computer science.

When you begin your studies of computer science you are introduced with terms and ideas which were all created around the idea of trying to model and represent solutions to problems in a provable, correct manner.

Alan Turing

Alan Turing, geniusly, presented us with the notion of Turing machines. These “machines”, allowed us to properly describe solutions, in a mathematically proven manner - for problems encountered (also) in the domain of computer science.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

From there grew an entire study around abstract computing machines (including Turing machines), named automata theory.

The domain of automata theory is wide, growing and most popular - due to it’s ability to produce models which are able to solve real-life problems.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

To some extent, automata theory is highly related to graph theory.

Combining the power of these two, we are able to design provable, distributed and efficient solutions to problems which otherwise would be too complex to represent and solve.

In this article, I will present you with Apache Storm (I will use the term “Storm” from now on - always referring to the Apache release of Storm) as an implementation of a distributed graph computation infrastructure.

Let’s get started!

Graph Computation as a Way to Reduce System Complexity

Graph computation as a way to reduce system complexity? After all the introduction about turing machines, automata theory and graph theory?

Well … yes.

Relying on a tested and proven model does not necessarily mean that using this model is as complicated as proving it.

For example, think of the following expression:

1 + 1 = 2

We all “know” it’s correct and are able to use it because someone else had already proven it to be true.

In our case, we are trying to take a known problem, and transform it into the shape of a computation graph, where each vertex is a computation unit. We “move” between vertices, according to the edges which connect them.

Let’s think of the following example:

We would like to implement an application which performs the following tasks:

- It receives as an input, an order request.

- If the order is valid, it sends a packaging and shipping request to the warehouse and notifies the client of a successful order placement.

- If the order is invalid, it notifies the client.

Looking at the task at hand as a computation graph, we can describe it as demonstrated below:

Thinking of the problem as a graph has some benefits.

To begin with, it's simpler for our human mind to comprehend the bigger picture, now that we have a picture :-).

Then, it encourages us to follow good and pragmatic software design principles, such as the separation of concerns principle. Each vertex does exactly only one thing.

Then again, it makes us look at the common things each vertex does and outsource it to our infrastructure.

For example, each vertex receives and possibly sends messages. Outsourcing the responsibility of handling incoming and outgoing messages in a fault-tolerant manner is very desirable.

Our deployment can also become more flexible this way - for example, we could deploy each computation unit of a separate machine and have the infrastructure worry about proper message delivery and distribution.

What about load-balancing and scalability? Could we rely on our “external” message delivery system for managing multiple instances of the same computation unit for us? Yes we can!

In case we are witnessing a bottleneck in the order validation process, could we instantiate an additional validation computation unit and have it handle some of the work? Yep.

Now, please keep in mind that we’ve described in our graph how each input message should be handled. We haven’t described anything about how to deploy it.

So, we’ve also separated the concerns of software correctness and software deployment.

It could very well be the case that we have one physical computation unit instantiated for each “logical” graph vertex except of the validation vertex which we will instantiate two computation units for.

The hints I’ve mentioned before about separation of concerns, utilizing a proper infrastructure which can handle interprocess communication for us, given different deployment desires (per organization / individual), in a fault-tolerant and scalable manner were aimed at making a point.

That point is that graph computation is indeed helpful and helps us think about software solutions while taking software deployment out of the equation - as long as we have a technology with proper infrastructure to do so.

Apache Storm provides us with both the ability to write our computations as graphs, as well as providing an inherent infrastructure which enables us to do so reliably and efficiently.

The Apache Storm Way

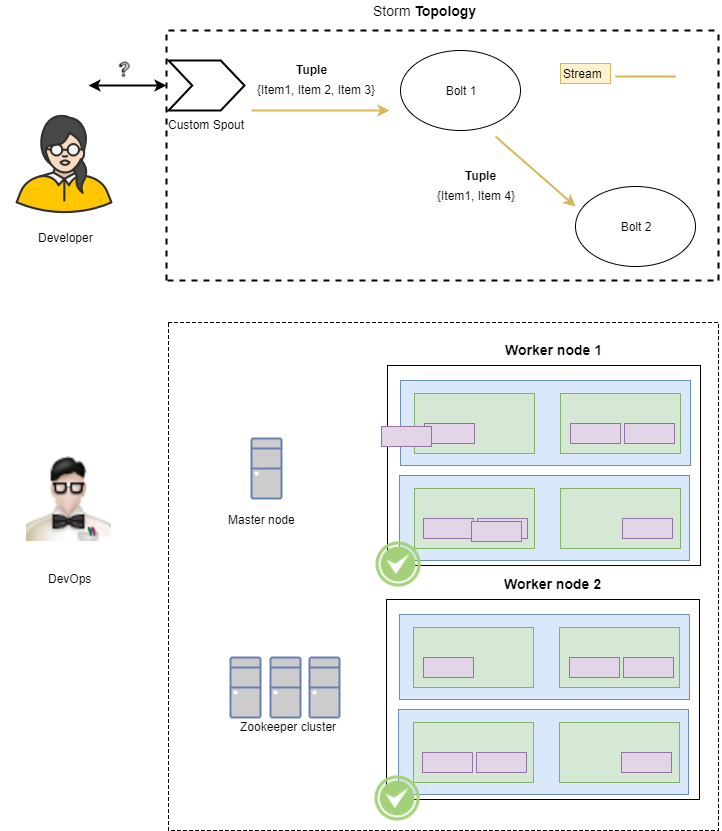

With Storm, our main application is called a topology.

Each topology represents an always-on application, which can receive input from data sources referred to as spouts.

A spout is a source of input messages, which are called tuples. A tuple is dynamically typed and it’s members can be of any type - as long as Storm “knows” how to serialize and deserialize these types.

Tuples are being passed among bolts, as defined by the topology. Each bolt can pass tuples to other bolts, only if they are connected to it. A bolt can modify a tuple or create a new one. It can also pass the incoming tuple as is or simply not pass anything at all.

The flow of tuples through spouts and tuples is referred to as streams. Multiple streams can co-exist in one topology. Each data stream is processed in parallel to other data streams. We will get back to this point later.

Storm is a great team player and integrates well with other technologies. It includes infrastructure which will enable you to work with Elasticsearch, Mongodb, Kafka, Redis, Kinesis and much more. In case you need something custom, that is also possible.

So, if I wanted to summarize “The Storm Way” in a sentence I would say that:

Apache Storm is a distributed technology, aimed at allowing developers to provide logical solutions to problems utilizing a graph computation model - while providing a mature and highly integratable infrastructure capabilities both “under the hood” (e.g. message load-balancing) and “on the shelf” (e.g. a ready to use Kafka Spout - just configure and consume data from Kafka).

Apache Storm Overview

In order to better understand how Storm works, we need to zoom out for a short while.

I am not going to perform a deep dive into the technology itself. However, if you do want to better understand the technology, including demos of deployment, integration with other technologies and monitoring, take a look at my course, here.

At the bird's-eye-view, let’s see how a Storm cluster is built. This will help us understand how it is able to provide us with the aforementioned infrastructure such as reliable messaging between our computation graph parts, as well as a certain degree of parallelism as I will explain a bit further down the road.

To begin with, the storm cluster is built from (not surprising) … nodes. These nodes can take on the form of either a master node, running the Nimbus daemon, or a worker node - running the Supervisor daemon.

The master node takes on the job of distributing work among the worker nodes. What work? The actual code that implements our graph computation, passed on to the Storm cluster as a topology.

How do the master node and the worker nodes know each other? Through Zookeeper. Zookeeper is a distributed service that serves as a reliable configuration and synchronization provider. To learn more about Zookeeper, including setup and integration demos, take a look here.

Ok, so we said that the master node is responsible of distributing code to worker nodes. However, there is an additional abstraction layer here: the worker process.

A worker process is responsible for executing a subset of the topology. Each worker process will instantiate executor threads which will host task instances. These tasks can be either spouts or bolts.

While it may seem rather laborious to understand, this structure is exactly what gives us the ability to distribute our logical computation graph among various physical machines, processes and threads, allowing our storm cluster to conserve our logical computational integrity in case of hardware failures.

A worker dies? No problem - we (the master node) will assign its work to another worker node.

Please notice that it seems like the master node is a single point of failure. It isn’t really. Even if the master node fails or crashes, our topology will keep executing. We will obviously not be able to submit a new topology to the cluster because it's the master node's responsibility to share code among worker nodes. However, our online computation will continue.

This undesirable situation is remedied by the fact that it is possible to define multiple master nodes in a Storm cluster (aka Nimbus H/A). In this way, a failing master node will be replaced with a healthy one.

I hope you better understand now how Storm completely separates between the logical notion of our computation graph (the topology, which is built from spouts and bolts with tuples flowing between them) and the physical hardware layer (master and worker nodes, zookeeper, worker processes and tasks running in executors).

This architecture is an enabler for separation of concerns among our teams. We can assign the task of handling the logical layer to the developers and the task of handling the physical layer to our DevOps engineers.

The engineers developing Storm gave thought to the aforementioned separation of concerns notion, and supplied the developers with a mean of running a topology locally, on the developer's machine.

Talking about developers - how about we look at some code?

Sample Topology - Let’s See Some Code

Ok, so some of you probably thought that when I gave the order validation, packaging, and shipment, my example wasn’t that good for demonstrating graph computation.

I disagree. Graph computation, just as any other model is a tool. As developers, software architects and/or VP R&D, we need to decide if this tool suits the task at hand. I claim that for high throughput ecommerce websites, Storm actually fits nicely as a stable backend.

Let’s see how we could implement the aforementioned use case as a Storm topology.

First, we need to setup a new project. I am demonstrating with a Maven project. I’ve added the following dependency to my pom.xml file:

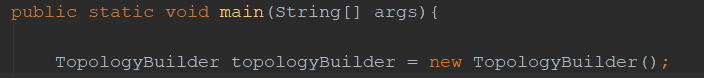

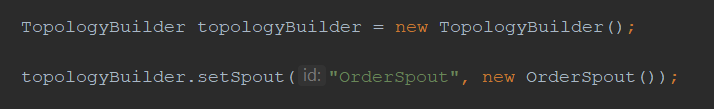

We will begin by creating a topology, using the TopologyBuilder provided by Storm:

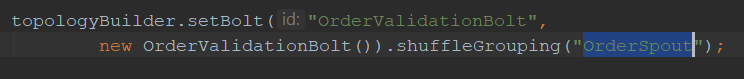

In order, to set topology spouts, we will invoke the setSpout method on the TopologyBuilder instance, passing it a spout id and a spout instance.

This is our entry point into our graph computation. In your case it could be a KafkaSpout, for example.

Now that we have information flowing into our system, we would like to digest it. Time to add some bolts to the topology.

Per each bolt we connect to the topology, we will provide the following information:

- Bolt ID, which uniquely identifies it in the topology.

- Its predecessor in the topology, together with a preferred grouping method.

- An optional stream ID.

2 and 3 will be covered shortly.

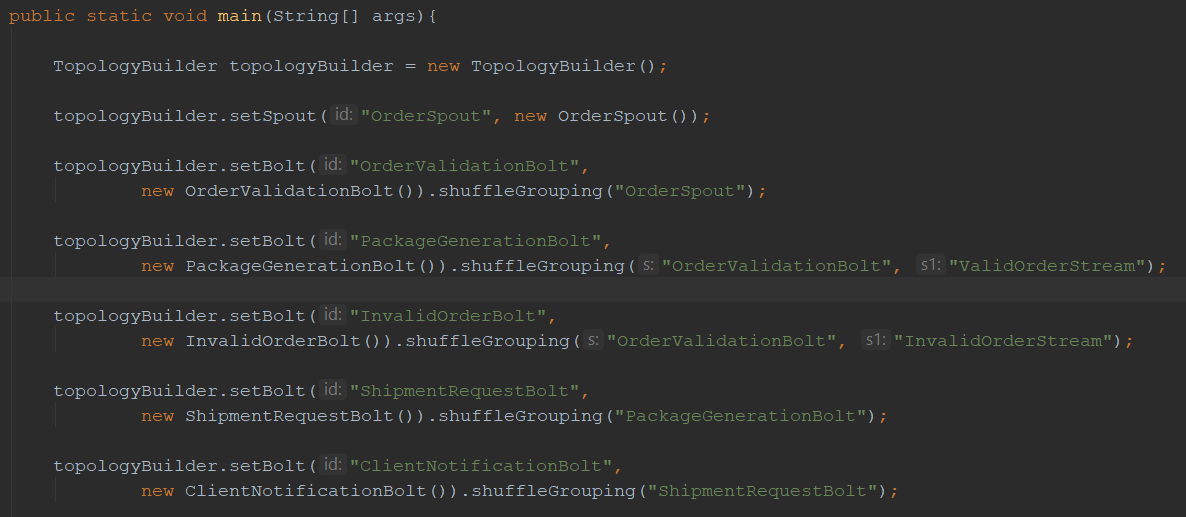

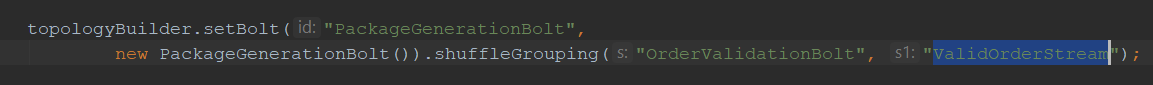

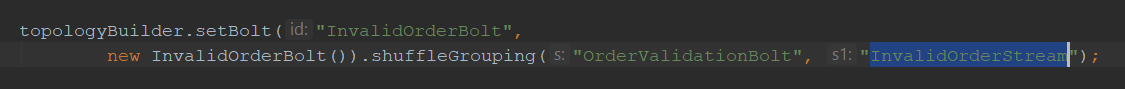

So, let's take a look at our topology, with all it’s bolts:

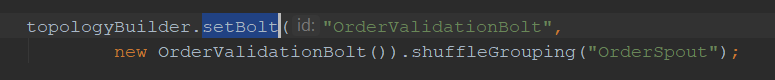

Each time I’ve added a bolt to the topology, I invoked setBolt.

Then, I named the bolt, and provided an instance for that bolt. That instance is a class implemented per each bolts required logic. I will review such a bolt shortly.

Per each bolt, we’ve connected it to another bolt or spout which will provide it with input.

In the case of the validation bolt, as two outcomes are possible (valid or invalid) - per each possible result we’ve created a bolt which listens to messages only on a particular stream (which the validation bolt is sending messages to).

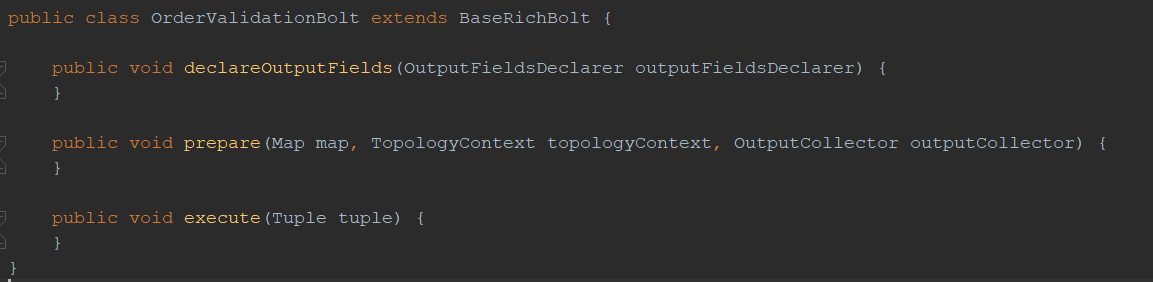

Now, let’s observe a bolt implementation. What are we required to implement in order to comply with Storm’s architecture?

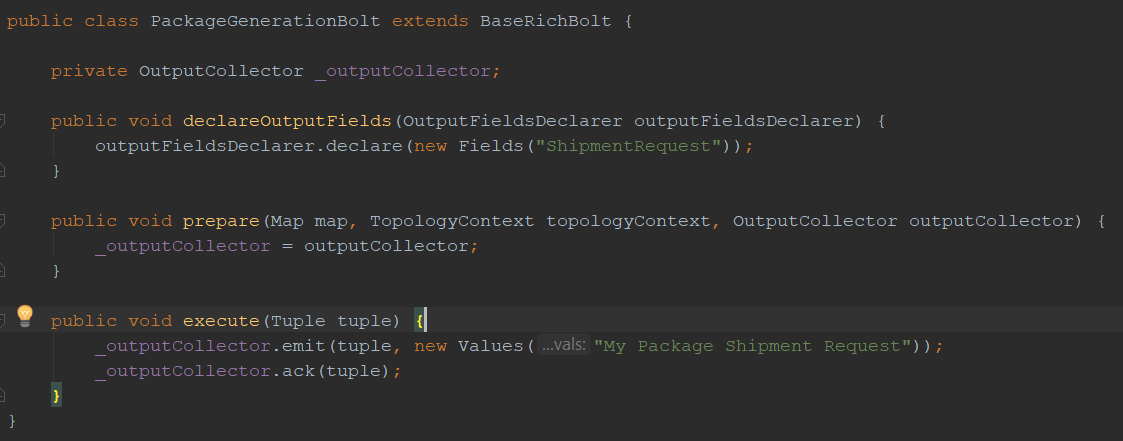

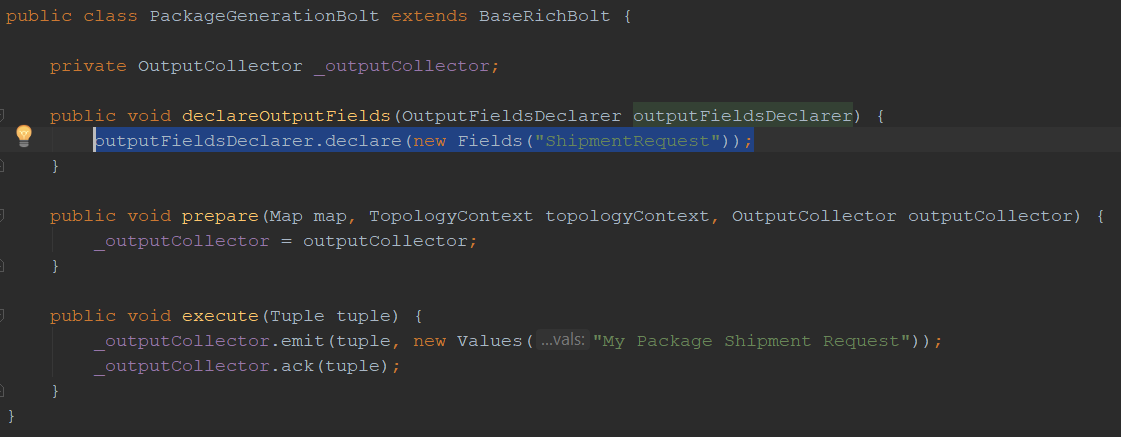

As can be seen here, I’ve extended the BaseRichBolt class. In order to comply with its definition, I must implement three methods.

The prepare method, as it’s name suggests, is a placeholder for us to do any required initialization required for the bolt for proper functionality once tuples arrive to it. In most cases, we will at least save our output collector reference to a local variable. The output collector allows us to emit new tuples to the following bolts.

It also allows us to acknowledge a tuple. Storm will consider any unacknowledged tuple as an unhandled data structure meant to be reprocessed.

The execute method will be invoked (by the Storm infrastructure) once per each tuple passed to us. Within the execute method we will consume the tuple, emit any new tuples in case we want to, and finally - acknowledge the incoming tuple.

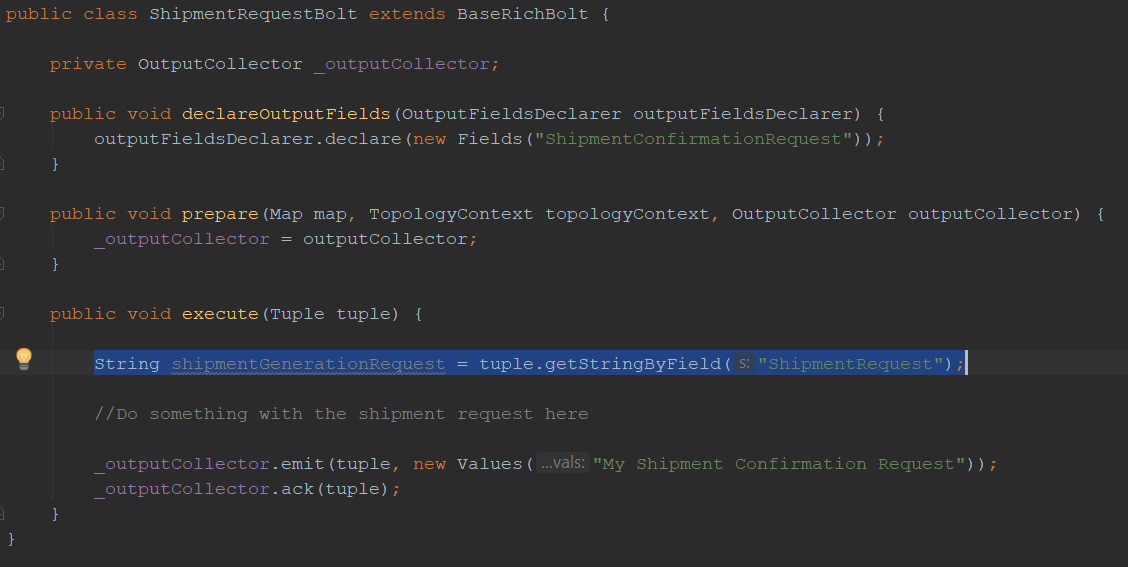

The declareOutputFields method is required when we want to pass a specific field to the next bolt(s). For example, the PackageGenerationBolt passes its shipment request in a field called “ShipmentRequest” to which the next bolt (ShipmentRequestBolt) knows how to refer:

At last, we would like to submit our topology to our cluster and run it. In our case, we are submitting to a local cluster, developed specifically for debug purposes:

Once our topology was tested and debugged, we can safely deploy it to our “real” Storm cluster.

That can be done in several ways.

In general, we need to package our topology into a jar file, together with all relevant dependencies, and pass it to our Storm cluster. That can be done utilizing the command line rather simply.

If you want to see a “real-life” demo of how that is done, check it out here.

So How Is My Computation Distributed?

Amazing! So now we understand that it is not so difficult to break down many computations into the logical and physical form of a graph, where vertices communicate in a “standard” form (serialized tuples).

We also understand how our code is being executed on the Storm cluster.

After we submit our topology to the cluster, packed as a jar file, the topology components (i.e. spouts and bolts) are deployed to various storm worker nodes (by the master node) and are being instantiated in worker nodes - encapsulated in task threads, living in executor processes.

The Storm infrastructure is aware of data streams flowing within the topology. This infrastructure also tracks tuple acknowledgment by bolts, providing us with a reliable messaging system.

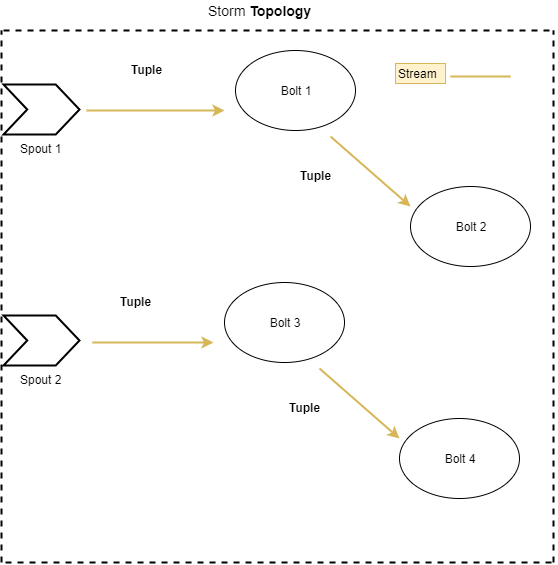

Inherent Parallelism: Streams as a Degree of Parallelism

One of the benefits of graph computation is that we can clearly visualize the separate computation paths in our application.

Take a look here:

Is there anything preventing us from processing the two different data streams in parallel? Not really. This is a perfect task for Storm!

A stream is a degree of parallelism in Storm. All stream tuples will flow through relevant bolts (as described by the topology), without knowledge of other streams in the topology.

A Bolt Has Several Instances

Good start, right? Different streams can and are processed separately and independently. However, there is another degree of parallelism — one which is at the task level. Being the great students that you are, you remember that a task can take the form of a spout or a bolt.

When defining a topology, we can declare the degree of parallelism we desire per spout or bolt.

Please notice that we do not want tasks to be spawned on-demand with no control! Too many tasks (i.e. threads) will introduce over-parallelism and possibly cause our cluster to “slow down” and eventually become unresponsive.

Before you use Storm's parallelizing capabilities, consider the degree of parallelism you are trying to achieve, given available resources.

Given that we have 3 Storm worker nodes, and we deploy a topology with a single spout with degree of parallelism set to 2 and 5 bolts with degree of parallelism set to 2 for each — we will have storm spawn 2 tasks for the spout and 5 * 2 = 10 tasks per the bolts.

That means that we will have 12 tasks which the storm cluster will try to spread across the 3 worker nodes evenly (I didn’t draw all the lines to avoid a mess).

Grouping as an Internal “Order Maker”

I promised I’ll get back to the concept of grouping.

We’ve previously seen that when creating a bolt, we’ve specified it’s “input” bolt:

But the way we’ve done so was unclear, as we’ve stated that we want a “shuffle grouping” with that bolt:

Strange, isn’t it? What does grouping have to do with the graph topology we set up earlier? Don’t all stream tuples simply flow from one bolt to the other?

Well, remember that spouts and bolts can have multiple instances, in order to parallelize our distributed computation.

While a spout or bolt is logically an atomic computation unit, it’s physical implementation isn’t necessarily.

Grouping is our way of defining the flow of tuples between two different topology elements. It will define how tuples flow between instances (tasks) of the input entity and the target entity.

For example, the “shuffleGrouping” will send tuples randomly to bolt instances.

As a reminder, when discussing grouping, we are talking about the flow of data between two entities, and only two entities.

Here, you can see how each tuple is transferred randomly to one bolt instance (task), from the PackageGenerationBolt to the ShipmentRequestBolt.

A most interesting grouping option is the “Fields” grouping, in which we specify specific fields by which we want to group our tuples. For example, we grouped our ShipmentRequestBolt to the PackageGenerationRequest based on the field “WarehouseId”. Due to this "Fields" grouping strategy, all tuples with the same WarehouseId value in an incoming tuple will always get directed to the same ShipmentRequestBolt task instance.

There are additional interesting grouping methods you can check here.

In Conclusion

Thanks for bearing with me through this short journey, examining the concept of graph computations in general and with Apache Storm in more specific details. While writing this article I kept in mind “keeping it simple”, assuming that once you’ve “got” the idea and understood the tool - you will be able to decide if a deeper examination of Storm is desirable. That is also the reason I’ve referred to additional reading and to my Pluralsight course.

We began this journey with understanding what graph computation is, and where it originated. In particular, we understood how profound a concept it is in the domain of computer science.

Once convinced (hopefully), we’ve moved on to discuss the benefits of a supporting infrastructure, in order to reliably implement our application as a graph computation.

We presented Apache Storm as such a technology.

Storm was reviewed at the levels - the logical level, the topology and the physical level - the physical cluster itself.

We understood how a topology is spread across the cluster and executed in the final abstraction layer of the physical level - the task.

Then - we’ve discussed how parallelism is provided is Storm - both at the stream level and at the specific task level (spout or bolt).

Looking at some code, I’ve tried to convey the simplicity and beauty of using Storm.

Hopefully I’ve succeeded in intriguing you.

Thank you very much for reading!

Kobi.

Advance your tech skills today

Access courses on AI, cloud, data, security, and more—all led by industry experts.