Data Structures in Swift - Part 1

Get started with this two part guide about the different built-in Swift collection types and how to implement the most common data structures in Swift.

Dec 14, 2018 • 20 Minute Read

Introduction

Why Data Structures?

Data structures are containers that hold data used in our programs. The efficiency of these data structures affects our software as a whole. Therefore, it is crucial that we understand the structurers available for us to use and that we choose the correct ones for our various tasks.

Structure

This is the first part of a two-part series on data structures in Swift.

In this tutorial, we’re going to talk about generics and the built-in Swift collection types. In the second part, we’ll take a look at some of the most popular data structures and how they can be implemented in Swift.

Generics

Generics are the means for writing useful and reusable code. They are also used to implement flexible data structures that are not constrained to a single data type.

Generics stand at the core of the Swift standard library. They are so deeply rooted in the language that you cannot and should not ignore them. In fact, after a while, you won’t even notice that you’re using generics.

Why do we need generics?

To illustrate the problem, let’s try to solve a simple problem: create types which hold pairs of different values.

A naive attempt might look like this:

struct StringPair {

var first: String

var second: String

}

struct IntPair {

var first: Int

var second: Int

}

struct FloatPair {

var first: Float

var second: Float

}

Now, what if we need a type which holds pairs of Data instances? No problem, we’ll create a DataPair structure!

struct DataPair {

var first: Data

var second: Data

}

And a type which holds different types, say a String and a Double? Here you go:

struct StringDoublePair {

var first: String

var second: Double

}

We can now use our newly created types:

let pair = StringPair(first: "First", second: "Second")

print(pair)

// StringPair(first: "First", second: “Second")

let numberPair = IntPair(first: 1, second: 2)

print(numberPair)

// IntPair(first: 1, second: 2)

let stringDoublePair = StringDoublePair(first: "First", second: 42.5)

print(stringDoublePair)

// StringDoublePair(first: "First", second: 42.5)

Is this really the way to go? Definitely not! We must stop the type explosion before it gets out of hand.

Generic Types

Wouldn’t it be cool to have just one type which can work with any value? How about this:

struct Pair<T1, T2> {

var first: T1

var second: T2

}

We arrived at a generic solution which can be used with any type.

Instead of providing the concrete types of the properties in the structure, we use placeholders: T1 and T2.

We can simply call our struct Pair because we don’t have to specify the supported types in the name of our structure.

Now we can write:

let floatFloatPair = Pair<Float, Float>(first: 0.3, second: 0.5)

print(floatFloatPair)

// Pair<Float, Float>(first: 0.300000012, second: 0.5)

We can even skip the placeholder types because the compiler is smart enough to figure out the type based on the arguments. (Type inference works by examining the provided values while compiling the code.)

let stringAndString = Pair(first: "First String", second: "Second String")

print(stringAndString)

// Pair<String, String>(first: "First String", second: "Second String")

let stringAndDouble = Pair(first: "I'm a String", second: 99.99)

print(stringAndDouble)

// Pair<String, Double>(first: "I\'m a String", second: 99.989999999999995)

let intAndDate = Pair(first: 42, second: Date())

print(intAndDate)

// Pair<Int, Date>(first: 42, second: 2017-08-15 19:02:13 +0000)

In Swift, we can define our generic classes, structures, or enumerations just as easily.

Swift Collection Types

Swift has some primary collection types to get us going. Let’s get a closer look at the built-in Array, Set, and Dictionary types.

Arrays

Arrays store values of the same type in a specific order. The values must not be unique: each value can appear multiple times.Swift implements arrays - and all other collection types - as generic types. They can store any type: instances of classes, structs, enumerations, or any built-in type like Int, Float, Double, etc.

Creating Arrays

We create an array using the following syntax:

let numbers: Array<Int> = [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42]

print(numbers)

// Output: [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42]

You can also use the shorthand form [Type] - this is the preferred form by the way:

let numbers1: [Int] = [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42]

Providing the type of the elements is optional: we can also rely on Swift’s type inference to work out the type of the array:

let numbers = [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42]

A zero-based index identifies the position of each element. We can iterate through the array and print the indices using the Array index(of:) instance method:

for value in numbers {

if let index = numbers.index(of: value) {

print("Index of \(value) is \(index)")

}

}

The output will be:

Index of 0 is 0

Index of 2 is 1

Index of 1 is 2

Index of 3 is 3

Index of 1 is 2

Index of 42 is 5

We can also iterate through the array using the forEach(_:) method. This method executes its closure on each element in the same order as a for-in loop:

numbers.forEach { value in

if let index = numbers.index(of: value) {

print("Index of \(value) is \(index)")

}

}

Mutable Arrays

If we want to modify the array after its creation, we must assign it to a variable rather than a constant.

var mutableNumbers = [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42]

Then, we can use various Array instance methods like for example append(_:) or insert(_:at:) to add new values to the array.

mutableNumbers.append(11)

print(mutableNumbers)

// Output: [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42, 11]

mutableNumbers.insert(100, at: 2)

print(mutableNumbers)

// Output: [0, 2, 100, 1, 3, 1, 42, 11]

If you use insert(at:) make sure that the index is valid, otherwise you’ll end up in a runtime error.

To remove elements from an array, we can use the remove(at:) method:

mutableNumbers.remove(at: 2)

print(mutableNumbers)

// Output: [0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 42, 11]

Again, if the index is invalid, a runtime error occurs. The gap is closed whenever we remove elements from the array. To remove all the elements, call removeAll():

mutableNumbers.removeAll()

print(mutableNumbers)

// Output: []

I’ve mentioned some of the most frequently used Array methods. There are plenty of other methods that you can use; check out the documentation or simply start experimenting with them in a Swift playground.

Arrays store values of the same type in an ordered sequence. Use Arrays if the order of the elements is important and if the same values shall appear multiple times.

If the order or repetition of elements does not matter, you can use a set instead.

Sets

There are two fundamental differences between a set and an array:

- the set provides no defined ordering

- a value can only appear once in a set

The Set exposes useful methods that let us combine two sets using mathematical set operations like union and subtract.Let’s get started with the basic syntax for set creation.

Creating Sets

We can declare a Set using the following syntax:

let uniqueNumbers: Set<Int> = [0, 2, 1, 3, 42]

print(uniqueNumbers)

// Output: [42, 2, 0, 1, 3]

Note that we can’t use the shorthand form as we did for arrays. Swift’s type inference engine could not tell whether we want to instantiate a Set rather than an array if we defined it like this:

let uniqueNumbers = [0, 2, 1, 3, 42] // this will create an Array of Int values

We must specify that we need a Set; however, type inference will still work for the values used in the Set. So, we can write the following:

let uniqueNumbers: Set = [0, 2, 1, 3, 42] // creates a Set of Int values

Let’s take a look at this example:

let zeroes: Set<Int> = [0, 0, 0, 0]

print(zeroes)

Can you guess the output? This is what we’ll see in the console: [0] The set will allow only one out of the four zeroes. Whereas if we use an array, we get all our zeroes:

let zeroesArray: Array<Int> = [0, 0, 0, 0]

print(zeroesArray)

// Output: [0, 0, 0, 0]

Be careful when choosing the collection type, as they serve different purposes. We can use the for-in loop or the forEach() method:

let uniqueNumbers: Set = [0, 2, 1, 3, 42]

for value in uniqueNumbers {

print(value)

}

uniqueNumbers.forEach { value in

print(value)

}

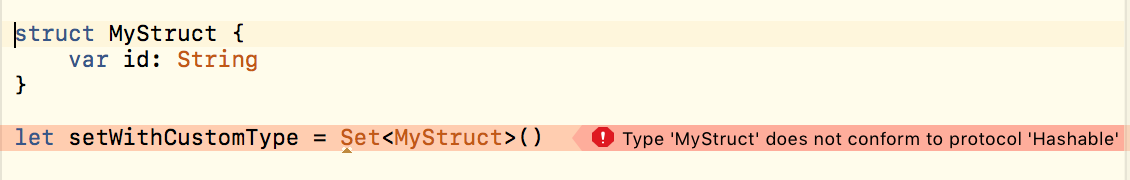

Hashable Values

A set cannot have duplicates. In order to check for duplicates, the set must be of a type that has a way to tell whether two instances are equal.

Swift uses a hash value for this purpose. The hash value is a unique value of type Int, which must be equal if two values are the same. In most languages, various object types have functions that produce a hashcode which determines equality. Swift’s basic built-in types are hashable. So, we can use String, Bool, Int, Float or Double values in a set. However, if we want to use custom types, we must implement the Hashable protocol.

Hashable conformance means that your type must implement a read-only property called hashValue of type Int. Also, because Hashable conforms to Equatable, you must also implement the equality (==) operator.

struct MyStruct: Hashable {

var id: String

public var hashValue: Int {

return id.hashValue

}

public static func ==(lhs: MyStruct, rhs: MyStruct) -> Bool {

return lhs.id == rhs.id

}

}

Now we can instantiate our Set of MyStruct elements and the compiler won’t complain anymore:

let setWithCustomType = Set<MyStruct>()

Mutable Sets

We can create mutable sets by assigning the set to a variable.

var mutableStringSet: Set = ["One", "Two", "Three"]print(mutableStringSet)// Output: ["One", "Three", "Two"]

We can add new elements to the set via the insert() Set instance method:

mutableStringSet.insert("Four")print(mutableStringSet)// Output: ["Three", "Two", "Four", "One"]

To remove elements from a set, we can call the remove() method:

mutableStringSet.remove("Three")

print(mutableStringSet)

// Output: ["Two", "Four", "One"]

If the element we are about to remove is not in the list, the remove method has no effect:

mutableStringSet.remove("Ten")

print(mutableStringSet)

// Output: ["Two", "Four", “One"]

The remove() method returns the element that was removed from the list. We can use this feature to check whether the value was indeed deleted:

if let removedElement = mutableStringSet.remove("Ten") {

print("\(removedElement) was removed from the Set")

} else {

print("\"Ten\" not found in the Set")

}

To remove all the elements in the set call removeAll():

mutableStringSet.removeAll()

print(mutableStringSet)

// Output: []

Alternatively, we could check whether the element exists using the contains() Set instance method:

if mutableStringSet.contains("Ten") {

mutableStringSet.remove("Ten")

}

print(mutableStringSet)

Set Operations

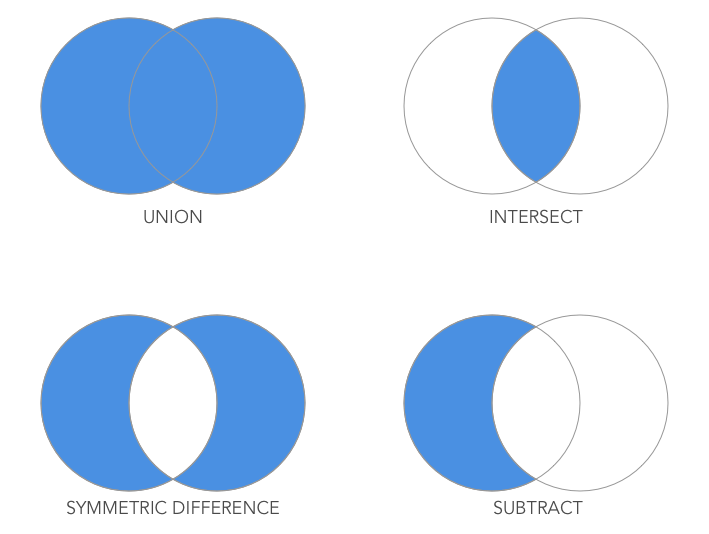

We can use the following Set operations to combine two sets into a new one:

- Union - Creates a new set with all of the elements in the two sets. If the same element exists in both sets, only one instance will appear in the resulting set.

let primeNumbers: Set = [11, 13, 17, 19, 23]

let oddNumbers: Set = [11, 13, 15, 17]

let union = primeNumbers.union(oddNumbers)

print( union.sorted() )

// Output: [11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 23]

[11, 13, 17, 19, 23] ∪ [11, 13, 15, 17] = [11, 13, 13, 15, 17, 17, 19, 23]

//After removing the duplicates, the result is [11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 23]

- Intersect - The result of calling the intersection() Set instance method is a set which holds the elements that appear in both sets.

let intersection = primeNumbers.intersection(oddNumbers)print(intersection.sorted)// Output: [11, 13, 17]

[11, 13, 17, 19, 23] ∩ [11, 13, 15, 17] = [11, 13, 17]

- Symmetric Difference - After invoking the symmetricDifference() method, the resulting set will contain elements that are only in either set, but not both.

let symmetricDiff = primeNumbers.symmetricDifference(oddNumbers)

print(symmetricDiff.sorted)

// Output: [15, 19, 23]

[11, 13, 17, 19, 23] ∆ [11, 13, 15, 17] = [15, 19, 23]

- Subtract - The result will contain those values which are only in the source set and not in the subtracted set. This output is known as the set difference.

11

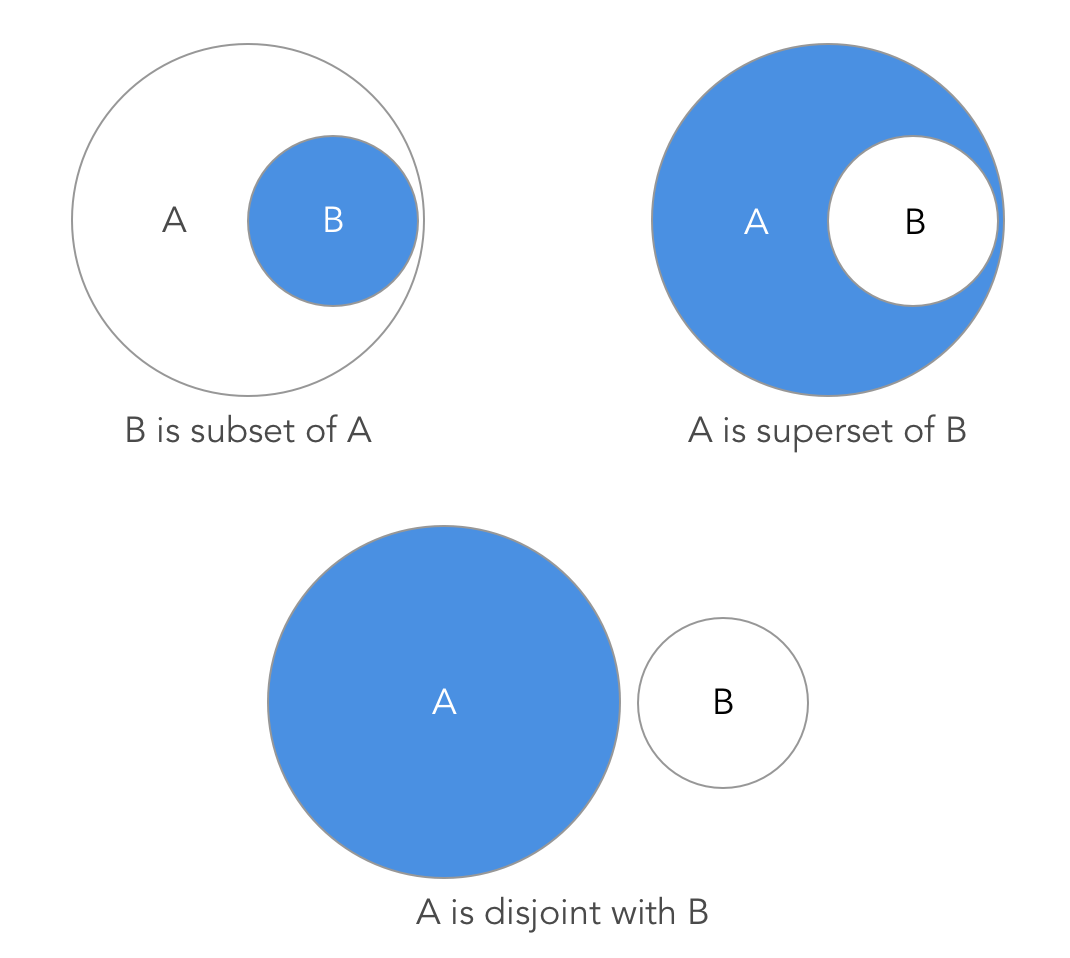

Set Membership Methods

The Set exposes methods to test for equality and membership:

- == - tests whether the values contained in both sets are all the same

- isSubset(of:) - checks whether the values from a set are contained in the other set

- isStrictSubset(of:) - returns true if the other set contains all the values from the set, but the sets are not equal

- isSuperset(of:) - checks whether the set contains all the values from the other set

- isStrictSuperset(of:) - checks whether the set has all the elements contained in the other set, but the sets are not equal

- isDisjoint(with:) - call to find out whether the two sets have no elements in common

Examples:

let numbers: Set = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

let otherNumbers: Set = [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]

if numbers == otherNumbers {

print("\(numbers) and \(otherNumbers) contain the same values")

}

// Prints: [4, 5, 2, 0, 1, 3] and [5, 0, 2, 4, 3, 1] contain the same values

let oddNumbers: Set = [1, 3, 5]

if oddNumbers.isSubset(of: numbers) {

print("\(oddNumbers.sorted()) is subset of \(numbers.sorted())")

}

// Prints: [1, 3, 5] is subset of [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

if numbers.isSuperset(of: oddNumbers) {

print("\(numbers.sorted()) is superset of \(oddNumbers.sorted())")

}

// Prints: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] is superset of [1, 3, 5]

let primeNumbers: Set = [2, 3, 5]

let otherPrimeNumbers: Set = [11, 13, 17]

if primeNumbers.isDisjoint(with: otherPrimeNumbers) {

print("\(primeNumbers.sorted()) has no values in common with \(otherPrimeNumbers.sorted())")

}

// Prints: [11, 13, 17, 19, 23] has no values in common with [11, 13, 17]

We discussed some of the most important capabilities of Sets. Hopefully this knowledge will make it easier to choose between a Set and an Array.

Dictionaries

Dictionaries - also known as hash maps - store key-value pairs and allow for efficient setting and reading of values based on their unique identifiers. Just like the other Swift collection types, the Dictionary is also implemented as a generic type, meaning that it can take on any data type.

Creating Dictionaries

To create a dictionary, we must specify the key and the value type.

- Using the initializer syntax

var numbersDictionary = Dictionary<Int, String>()

- Using the shorthand syntax

var numbersDictionary = [Int: String]()

- Using dictionary literals Swift can infer the type of the keys and the values based on the literals

var numbersDictionary = [0: "Zero", 1: "One", 10: "Ten"]

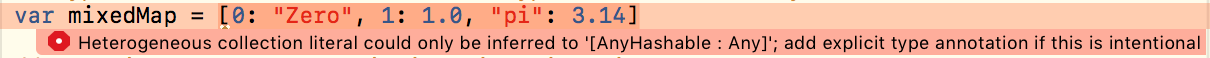

Heterogeneous Dictionaries

When creating a dictionary, the types of the keys and the values is supposed to be consistent - e.g., all keys are of type Int and all the values are of type String.

Type inference won't work if the type of the dictionary literals is not consistent.

However, there are cases when we do need dictionaries with different key and value types. For instance, when converting JSON payloads or property lists, a typed dictionary won't work.

Alright, let’s try the following:

var mixedMap: [Any: Any] = [0: “Zero”, "pi": 3.14]

Now, the compiler complains about something else: "Type 'Any' does not conform to protocol 'Hashable'"

The problem is that the Dictionary requires keys that are hashable - just like the values used in a Set.

AnyHashable

Starting with Swift 3, the standard library introduced a new type called AnyHashable. It can hold a value of any type conforming to the Hashable protocol.AnyHashable can be used as the supertype for keys in heterogeneous dictionaries.

So, we can create a heterogeneous collection like this:

var mixedMap: [AnyHashable: Any] = [0: "Zero", 1: 1.0, "pi": 3.14]

AnyHashable is a structure which lets us create a type-erased hashable value that wraps the given instance. This is what happens behind the scenes:

var mixedMap = [AnyHashable(0): "Zero" as Any, AnyHashable(1): 1.0 as Any, AnyHashable("pi"): 3.14 as Any]

Actually, this version would compile just fine if we typed in Xcode - but the shorthand syntax is obviously more readable.

AnyHashable’s base property represents the wrapped value. It can be cast back to the original type using the as, as? or as! cast operators.

let piWrapped = AnyHashable("pi")

let piWrapped = AnyHashable("pi")

if let unwrappedPi = piWrapped.base as? String {

print(unwrappedPi)

}

Accessing and Modifying the Contents of a Dictionary

We can access the value stored in a dictionary associated with a given key using the subscript syntax:

var numbersDictionary = [0: "Zero", 1: "One", 10: "Ten"]

if let ten = numbersDictionary[10] {

print(ten)

}

// Output: Ten

We can also iterate over the key-value pairs of a dictionary using a for-in loop. Since it’s a dictionary, items are returned as a key-value touple:

for (key, value) in numbersDictionary {

print("\(key): \(value)")

}

We can access the dictionary's key property to retrieve its keys:

for key in numbersDictionary.keys {

print(key)

}

The value property will return the values stored in the dictionary:

for value in numbersDictionary.values {

print(value)

}

To add a new item to the dictionary, use a new key as the subscript index, and assign it a new value:

numbersDictionary[2] = "Two"

print(numbersDictionary)

// Prints: [10: "Ten", 2: "Two", 0: "Zero", 1: "One"]

To update an existing item, use the subscript syntax with an existing key:

numbersDictionary[2] = "Twoo"

print(numbersDictionary)

// Prints: [10: "Ten", 2: "Twoo", 0: "Zero", 1: "One"]

You can remove a value by assigning nil for its key:

numbersDictionary[1] = nil

print(numbersDictionary)

// Prints: [10: "Ten", 2: "Two", 0: "Zero"]

You can achieve the same result - with a little more typing - using the removeValue(forKey:) instance method:

numbersDictionary.removeValue(forKey: 2)

print(numbersDictionary4)

// Prints: [10: "Ten", 0: "Zero"]

Finally, removeAll() empties our dictionary without remorse:

numbersDictionary.removeAll()

print(numbersDictionary)

// Output: [:]

Conclusion

In this tutorial, we've covered the built-in Swift collection types.

Stay tuned for Data Structures in Swift Part 2. We’re going to talk about some popular data structures and we’ll implement them in Swift from scratch. Hopefully this will help you pick the correct data structure when the time comes!

In the meantime, you may want to check out my Swift courses on Pluralsight.

Thanks for reading and Happy Coding!

Advance your tech skills today

Access courses on AI, cloud, data, security, and more—all led by industry experts.