Software Delivery Using Test Driven Development (TDD)

In this free guide, you'll learn what Test Driven Development (TDD) is, its origins, why you should use TDD and more. Learn what tools best support BDD methodology.

Dec 15, 2018 • 12 Minute Read

Introduction

At some level, we can see sequences in all things we do – logically speaking. If I were to build a house, I'd need to first lay the foundation and then the walls – followed by the roof. I cannot do the roof before starting on the foundation.

Likewise, in the software development world, you first gather requirements, analyze them, design (HLD followed by LLD), come up with user stories, write some code, write test cases, execute your tests, revise, repeat, and eventually deploy. Shuffling the sequences of these activities is like building the roof before the foundation. However, this is exactly what we are set out to do in Test Driven Development.

What Is Test Driven Development?

Test Driven Development (TDD henceforth) is an iterative process in which test cases are written before a solution is implemented. This practice is contrary to the tradition involving coding first and testing second.

By writing the unit test case first, the developer is setting a target that is in sight. The unit test cases are meant to cover a small portion of the functionality. Once the "target" is set using the test cases, the developer will be able to write just enough code to make the test case pass and no more.

After the unit test passes, the developer can write the next unit test case, create a new target, and implement a solution that that meets the goal.

Thus, we can see that designing tests first helps make the entire development process smoother and more efficient, by allowing the coder to set sights early and code just enough to meet the necessary requirements. In fact, the more iterations before deployment, the stronger the benefits of TDD, as unit tests are applied over and over, ensuring that new features do not corrupt old ones.

So, in this iterative process, the test cases guide the developer in writing the code, giving this methodology its name: Test Driven Development.

TDD's Origins

When did TDD become a thing? This is a difficult question to answer because there is no definite answer.

Usually, TDD is coupled with agile project management as agile also seeks to work in iterations and believes in building using smaller bits. But the principle of writing test cases before writing code dates back to 1950s.

Kent Beck, who is credited for creating Extreme Programming, is a major backer of TDD methodology – hence the revival of TDD. He refers to TDD as rediscovery in the context of agile development.

Beck writes that the principle of TDD is quite old; it was employed during the age of mainframes. The practice that was followed by developers was to write down the expected output and then write the programs on punch cards. This was effective because the time they got to play with systems was limited, making this the best possible way for efficient use of their time. The output achieved on mainframes were compared to the documented output, and this would tell developers of the time if their program worked or not.

In the rediscovery phase, TDD was re-introduced by the Smalltalk community on their SUnit framework. When Java took off, JUnit framework was the tool employed for executing automated unit tests, and Beck was one of the developers of JUnit. Due to the commonalities between the unit test framework, agile revolution, and Beck, TDD was reintroduced into the mainstream yet again.

The TDD Process

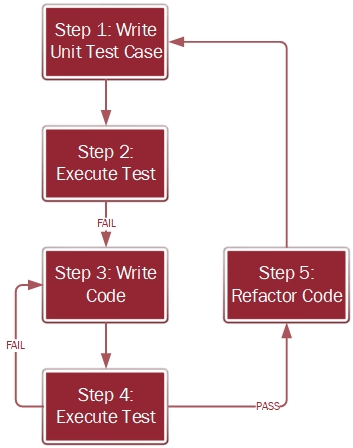

At a high level, the process to develop a software using TDD is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1: Process for Developing Software using TDD

Step 1: Write Unit Test Case

As mentioned earlier in the post, the first activity that you do in TDD is to write a unit test case. To reiterate, the unit test case must be as small as possible, and still be able to be independently tested.

Let’s say that I am developing a login page for an application. The login page has a logo in the header section followed by fields for username and password. Finally, there is a submit button to input the credentials.

In step 1, I start with the unit test case for the logo that I am going to place on the web page. Nothing more nothing less.

Step 2: Execute Test

Now, I have a unit test case and absolutely no code. Yet, I am going to execute the test case. Why? In TDD, you always write code for a failing test, and this is the reason why we execute the test case knowing full well that there is no code to support it.

Executing the test case without code also provides the insurance that the developer does not get carried away by the need to have the code in place before writing the test case. It is an additional layer of control that ensures that TDD is followed true to the spirit of it.

Step 3: Write Code

After the test has failed, then you write just enough code to execute the test case successfully. It is a common practice among developers to write plenty of code, more like a novel rather than the bullet points that we are looking for in TDD. You should not write more code than needed.

Step 4: Execute Test

Now that we have the code that is needed to successfully pass the unit test case created in Step 1, we execute the test again. If the test fails, it indicates that the code developed is not sufficient to run the test case. Go back to Step 3 to rework on the code.

If the test passes, the code meets the unit test controls, and can now proceed to Step 5 for refactoring.

Step 5: Refactor Code

Refactoring is an activity where you make the code efficient. You do not change the functionality, but rather alter the internal dynamics to enhance the performance. Some examples include identifying and removing duplicate and dead pieces of code, simplifying nested classes, and consolidating conditional expressions.

The code that has passed the unit test in Step 4 is put through the process of refactoring where the code is made efficient.

After refactoring, the developer picks up the next piece of unit test case, possibly the username field in the login page they're developing. They write the unit test case for the username field and repeat Steps 1 through 5. The process iterates until the feature or software is fully developed.

Why Employ TDD Methodology?

The code that comes out of this process is clean. It is free from bugs because the TDD methodology tests guides and hand-holds the development lifecycle. It is an effective arsenal against defects, which are otherwise major problems plaguing the software development industry. I am not implying that we are going to write 100% defect-free code, but TDD's defect rate is far lesser than the alternative.

Code coverage is a measure that we use in software development to identify the percentage of code that is tested. If every single line of the code is covered under the test cases, then the code coverage measured will be 100% - which is the target in ideal conditions. This is a necessary evil because you don’t want to introduce any lines of code that haven’t been scrutinized yet. However, many organizations insist on a lower number ranging between 90-95% of code coverage. Tools such as SonarQube and Atlassian Clover help you in the code coverage measurement.

With TDD however, it is possible to achieve 100% code coverage because you first write the test case and write just enough code to make the test case pass.

Are There Any Downsides to TDD?

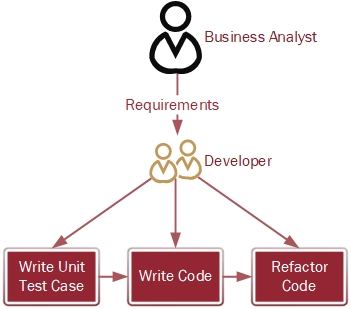

In an earlier section, I took you through the process involving TDD. Now, let us see who all are involved in the TDD methodology – represented in figure 2.

Figure 2: TDD Role Play

In a standard TDD project, a business analyst will get the requirements from the customer or a product owner and pass it onto the developer. The developer, based on the understanding of the requirements, creates and executes unit test cases and writes the code. Once the test execution is successful, the developer will refactor the code and repeat the TDD process for the tasks and user stories assigned to him.

The weak link in the process lies in the developer understanding the requirements. Suppose the business analyst explains that the customer’s requirement is to develop an account management system, the developer can misinterpret the requirements and develop something totally different, such as a customer relationship management system.

As you can see in the roleplay diagram, no testers are involved in TDD. The developer writes the test case and also develops the code. So, there is less validation of the requirements throughout the cycle than there is when testers are a part of the process.

Swaying away from the requirements is a costly mistake, and often ends up in hours of reworking the problem. This costs money, delays project timelines, and frequently angers the customer. According to me, this is the major downside of the TDD methodology: TDD makes it easier to make mistakes in understanding the requirements and continuing the coding process unchecked in this regard.

There are other alleged drawbacks, such as the process taking too much effort and time from a single individual. However, in that aspect, I believe that there is value in writing the test cases first and achieving clean code and code coverage. Having accurate code and focused development, in my mind, justifies the overhead effort and time spent.

Additionally, some say that the unit tests look to concentrate on the individual classes and functions rather than the overall user stories and customer requirements on a whole. I agree that the unit test cases work at a micro-level and may not assess requirements holistically. This problem is solved by methodologies that I am going to introduce in the next section.

Alternatives to TDD

The drawbacks I discussed in the previous section generally get addressed by the upgraded version of TDD. The most prominent upgrades to standard TDD are ATDD and BDD.

ATDD

ATDD, or Acceptance Test Driven Development, offers a couple major improvements over TDD. First, instead of writing unit test cases, acceptance test cases are written when user stories are written, and then the code is developed. Second, the test cases are written by the tester and the code is developed by the coder – which adds validation that the code meets the customer's expectations as defined by the business analyst.

However, even ATDD has some drawbacks. What if both the tester and the coder understand the requirements incorrectly? We may need another layer of control and validation. This layer is provided by the Behavioral Driven Development (BDD) methodology.

BDD

In BDD, acceptance test cases are developed, but there is a significant addition to the way requirements are obtained. The business analyst is expected to provide requirements along with relevant examples for each one of them. Through the use of these examples, the tester and the coder can build the requirements more accurately.

The next major difference when considering BDD is that BDD test cases are not written in the usual scripting language. Rather, forms of natural languages such as Gherkin is employed. Using a natural to write acceptance test cases will equip the business analyst, product owners, and customers to validate against the requirements. This helps void any discrepancies between the code and its output but adds a layer of complexity to the development process as code needs to now meet Gherkin requirements.

Tools That Support BDD Methodology.

Today most projects that are running on TDD are switching over to BDD. BDD is attractive because of the ease in which the acceptance test cases can be prepared and it acts as a natural bridge between the development teams and the customers. The proximity between the two enhances communication exchanges and reduces friction coming out of black boxes and delays.

Although BDD stands on its own today, it has taken its roots from the TDD methodology. The principles of TDD invented decades years ago continue to drive the industry through the development methodology's variants.

Advance your tech skills today

Access courses on AI, cloud, data, security, and more—all led by industry experts.